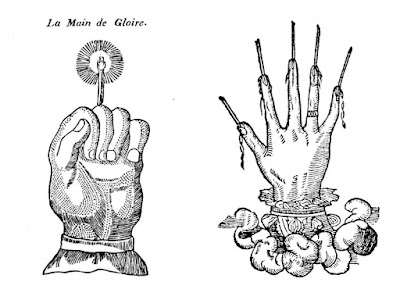

Superstitions and symbols surrounding the corpse have existed for millennia in cultures throughout the world, with the body of the criminal possessing a bevy of folklore. During the sixteenth century, the mandrake which typically grew beneath the gallows of Europe was believed to be imbued with magical properties as the blood and other bodily fluids from the executed dripped onto the foliage. In fact, the Gypsy princess in Ludwig Achin von Arnim’s novella Isabella of Egypt (1812) uses the mandrake below her father’s gallows to summon a Mandragore to help her achieve her ultimate goal of marrying the prince.[1] During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in turn, the hanged man’s body became the focus of a medical movement concentrated around gallows cures, which asserted contact with the corpse of a recently executed corpse could heal a variety of ailments, including swelling.[2] Indeed, the convict’s hand featured prominently in gallows cures and even developed its own superstitions among fellow criminals. Although the particulars vary (some versions of the folklore required the item to be greased and set aflame while others had it merely hold a candle made of human fat), the Hand of Glory served as a good-luck charm which protected robbers as they pilfered houses and was featured in popular fiction like Walter Scott’s The Antiquary (1816) and Richard Harris Barham’s The Ingoldsby Legends (1840).[3]

Works Referenced

Davies, Owen, and Francesca Matteoni. “‘A Virtue Beyond All Medicine:’ The Hanged Man’s Hand, Gallows Tradition and Healing in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century England.” Social History of Medicine 28.4 (2015): 686-705.

Tarlow, Sarah, and Emma Battell Lowman. Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

____________________

[1] Tarlow and Lowman, 226-227.

[2] Davies and Matteoni, 686-705.

[3] Tarlow and Lowman, 224-226.

No comments:

Post a Comment