$15 - $20 (based on 2017 prices)

Makes one candlestick

While building the pumpkin dolls for 2017’s haunt, I purposefully reserved one of the heads for this project. I had seen several concepts for old dolls used as candle holders and decided to fabricate my own version to incorporate into the theme. Since using fire in a haunt is never a wise idea, I substituted a real candle with an LED one.

- One candlestick

- One 10 oz. can of interior/exterior, fast-drying spray paint in metallic silver

- One small vinyl doll head

- One 2 oz. bottle of acrylic paint in flat black*

- One 2 oz. bottle of acrylic paint in flat brown*

- One 2 oz. bottle of acrylic paint in flat gray*

- One 2 oz. bottle of acrylic paint in steel gray*

- One 2 oz. bottle of acrylic paint in hot cocoa*

- One 2 oz. bottle of acrylic paint in flat red*

- One 8 oz. bottle of wood glue*

- One battery-operated LED candle

- One hot glue gun and glue sticks

- One 0.44 oz. bottle of clear nail polish*

1. On a newspaper-lined surface in a well-ventilated area, apply a few even coats of metallic spray paint to the candlestick. I used two, but you may apply more or less depending on your desired coverage. If you use a glass holder, roughen its surface with sandpaper to help the spray paint adhere.

2. Use a brush with splayed bristles to create an aging effect around the base and stem of the holder. I found that working from dark to light (i.e. black to steel gray to flat gray) produces the best results.

3. Insert the LED candle into the candlestick and use a permanent marker to indicate where the top of the holder rests. This will serve as a guide for the process in step five.

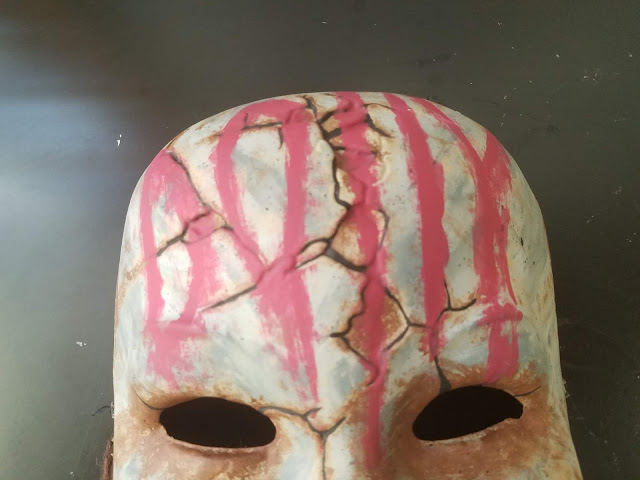

4. On a newspaper-lined surface in a well-ventilated area, crackle paint the doll’s head. To do this, begin with a base coat of black paint and, once that has dried, use a thick brush to smear a smattering of wood glue onto the prop. Try not to over think your application (a random pattern produces the best results). Let the glue sit for a minute to become tacky and then cover the head with a coat of hot cocoa paint. As the glue and paint dry, they will form cracks. To further the aging process, give the prop a light smudging of brown paint to simulate dirt. If you want an additional level of creepiness, sew the doll’s eyes and mouth with black thread.

5. Use a sharp knife to cut a hole in the top of the head large enough to accommodate the candle. You may have to gradually trim the opening until the candle passes easily through it. Once this is done, feed the candle through the hole and ensure the base of the head sits flush with the mark from step three.

6. Using hot glue, give the candle extra girth by building up layers and piping drips of wax down the sides and onto the head. I found that pumping the glue along the top of the candle and allowing it to naturally run downward creates the best results.

7. Apply three coats of red paint to the candle. I used three because I wanted a deep, vibrant red to contrast with the dull blacks and browns of the head. You, of course, are free to use fewer (or more) coats based on your chosen appearance for the prop.

8. To make the candle look waxy, cover the red paint with a layer of clear nail polish. If you want the candle to seem old and unused rather than freshly melted, do not add the nail polish, but give the candle a light brushing of brown paint to mimic dust.

9. Insert the remaining portion of the LED candle into the holder. Since the prop separates at this junction, you can easily access the on/off switch and battery compartment.

*You will not use the entire bottle’s content for this project.