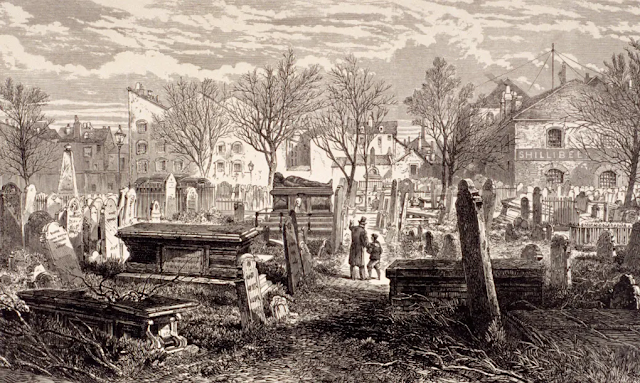

As the social elite deserted cemeteries, the rising bourgeoisie, comprised of craftsmen and laborers, seized control of the territory and, “no longer content simply to sleep in sanctified ground with no thought of the memory they left behind them,” used their modest means to purchase permanent plots from the church and erect gravestones that began as simple crosses and evolved into elaborate markers modeled after the private monuments of the upper echelons.[1] This act, Ariès reveals, weakened the connection between church and cemetery, reverted the graveyard back to a specialized place for burial (a concept not maintained for a thousand years), and began the gradual move back to the outskirts of the community.[2] Part of this migration, in turn, was driven by the insidious conditions caused by cemetery neglect in the middle of the eighteenth century, with overwrought clergy incapable of keeping pace with growing maintenance and dereliction breeding a slew of sanitary issues, including water contamination, infestations of flies spoiling nearby gardens and farms, air from the common graves leaking into the cellars of neighboring homes, and the effluvium of decay, chiefly during sweltering summer months, plaguing the local residents.[3] While administrative reports like Grande et Nécessaire Police (1619) first brought the problems to light during the seventeenth century, serious legislature was not introduced until a century later, with the Decree of the Parliament of Paris of March 12, 1763, for instance, making demands for improvement yet failing to ensure their applications.[4] Despite these governmental holdups, the relocation of burial grounds outside of city limits continued and, by the nineteenth century, it fostered the creation of rural monuments which served as fashionable resting spots for the dead and popular retreats for the living, who flocked to their park-like grave gardens and elaborate memorials to both honor the deceased and cherish each other through social interactions.[5] In doing so, Ariès reveals, the cemetery readopted its communal nature once established in the Middle Ages.[6]

Works Referenced

Ariès, Philippe. The Hour of Our Death: The Classic History of Western Attitudes Toward Death Over the Last One Thousand Years. 1977. Trans. Helen Weaver. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2000.

____________________

[1] Ariès, 272. [2] Ariès, 320-321.

[3] Ariès, 348-352.

[4] Ariès, 479-491.

[5] Ariès, 531-536.

[6] Ariès, 555-556.

[6] Ariès, 555-556.